We’ve all seen it. The form letter: the polite, generic language letting us know that our piece, book, essay, or whatever just “is not a good fit” or “not what we’re looking for right now.” Best of luck, best wishes, etc. Writers get used to the sting of rejection when they’re brave enough to get their work out there. And they are, you are brave for gathering the courage to do it! But of course, rejection still sucks. You can sit at a desk pounding on a keyboard for years, keeping your Soul on the Page all to yourself and finally start to believe, just maybe, someone will want to publish this for it all to add up to what feels like, well, nothing. This is the far more common occurrence.

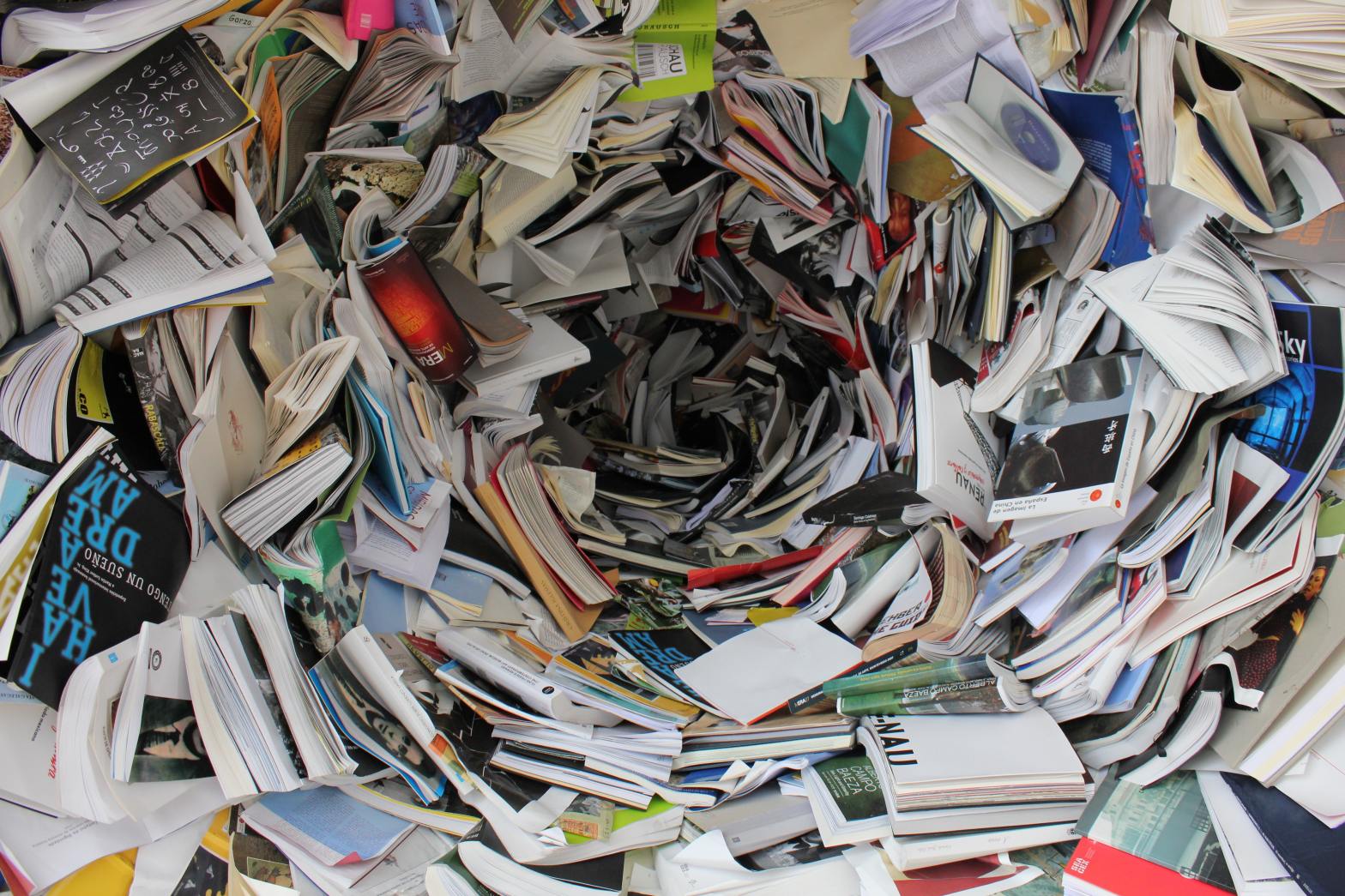

When I started my first “real job” in book publishing as an editorial assistant in 2016, I came in to an office full of rejection letters that needed to be sent out. The stack of papers was over a foot tall with submissions and corresponding form instructions for each. The previous EA had fallen behind on everything, and rejections fell to the bottom of the priority list, so they must have kept piling up.

As I caught up on getting the letters sent out, I tried to emotionally distance myself from the hopeful writers who’d allowed themselves to be vulnerable enough to submit their work. We had four or five standard form letters, but most of the time used one template. We responded in whatever method possible: if the writer did not provide an email address, we sent them snail mail. Once, a gentleman showed up to the office in person wanting to speak to someone about their book, and the introverts of editorial scattered like birds from a shaken tree.

I received several cold calls over the years, one from a teacher who wanted to know how she could get her students’ poetry published. Even after I told her we did not publish poetry books, she still read a sample or two to see if it piqued my interest. A self-published science fiction author once sent five or six printed volumes of their series, even though we were a nonfiction publisher. The books sat in my office for months before I found the time to ship them back.

Another time, an elderly gentleman emailed me every day to see if his proposal had been viewed yet. He finally emailed me on his eightieth birthday to let me know what day it was, essentially implying he did not know how much longer he would be around. We got him his rejection letter.

The previous anecdote is a good example of why a rejection is still better than no reply at all, but it doesn’t hurt any less. The responses writers get are rarely thorough enough for us to understand why our work was not accepted, and we’re left to play guessing games with our own insecurities and self-doubt as to why it shouldn’t be published. In my years working in editorial, I had a few letters here and there to transcribe in which our editor-in-chief would provide detailed advice as to how the writer should pitch their book elsewhere. But knowing how many submissions every publishing company and agent receive in any given week, it’s no wonder ninety percent of us just get form letter.

As I made my way through the coursework of my book coaching program, I learned about crafting a book with a solid, clear purpose and structure as well as developing a strong proposal that will show agents and publishers that you know exactly what you’re doing. Unfortunately, it’s not all about how passionately we love to write or how beautifully we may do it. There are so many other elements and efforts involved in publishing a book. A book coach can help you with every stage of that process. We can take a look at a rejected manuscript sample and assess the reasons why it was rejected, help you perfect your book proposal, and create a multi-step pitch plan.

I have learned that there are some very simple, specific reasons why an agent or publisher will reject your work. To learn more, go get my FREE guide to the Top Ten Reasons Your Book Proposal Keeps Getting Rejected.

One thought on “Rejection Letters: My Lessons from Editorial Assistant to Book Coach”